CONSOLABLE / IMMORTAL?

3.10 The beyond and the ancestors

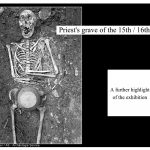

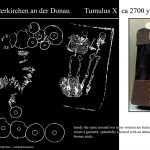

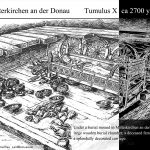

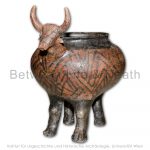

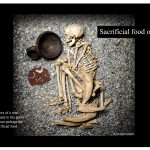

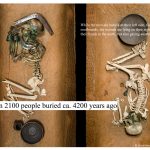

The beliefs in the beyond are very diverse. It is an alternative world of the dead, as opposed to the world of the living. The beyond is also a realm of the dead, where the dead reside (the Greek and Roman Underworlds, the Underworld in Norse mythology or of the ancient Egyptians, etc.) The beyond are specific, difficultly accessible places on the Earth, like mountains, caves, and forests. It is a subterranean world, the Underworld or Heaven. The beyond can be situated anywhere. In the beyond, there could be salvation. But it can also hold damnation. Ancestors possess a moral exemplary function, and can mediate between the worlds of the living and the dead. This function is for instance carried by saints in catholic Christianity, like the ʻFourteen Holy Helpersʼ. The most important rite in ancestor worship in Madagascar, is the festival of ʻthe turning of the bonesʼ, called ʻFamadihanaʼ. An example from ethnology is the tight connection with the ancestors at Nias in Indonesia.

1 Kommentar. Hinterlasse eine Antwort

Hallo, dies ist ein Kommentar.

Um mit dem Freischalten, Bearbeiten und Löschen von Kommentaren zu beginnen, besuche bitte die Kommentare-Ansicht im Dashboard.

Die Avatare der Kommentatoren kommen von Gravatar.